-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 12

/

Copy path02_intro.Rmd

1901 lines (1150 loc) · 67.5 KB

/

02_intro.Rmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

754

755

756

757

758

759

760

761

762

763

764

765

766

767

768

769

770

771

772

773

774

775

776

777

778

779

780

781

782

783

784

785

786

787

788

789

790

791

792

793

794

795

796

797

798

799

800

801

802

803

804

805

806

807

808

809

810

811

812

813

814

815

816

817

818

819

820

821

822

823

824

825

826

827

828

829

830

831

832

833

834

835

836

837

838

839

840

841

842

843

844

845

846

847

848

849

850

851

852

853

854

855

856

857

858

859

860

861

862

863

864

865

866

867

868

869

870

871

872

873

874

875

876

877

878

879

880

881

882

883

884

885

886

887

888

889

890

891

892

893

894

895

896

897

898

899

900

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

911

912

913

914

915

916

917

918

919

920

921

922

923

924

925

926

927

928

929

930

931

932

933

934

935

936

937

938

939

940

941

942

943

944

945

946

947

948

949

950

951

952

953

954

955

956

957

958

959

960

961

962

963

964

965

966

967

968

969

970

971

972

973

974

975

976

977

978

979

980

981

982

983

984

985

986

987

988

989

990

991

992

993

994

995

996

997

998

999

1000

# Managing data and code {#git_bash}

```{r include = FALSE}

# Caching this markdown file

knitr::opts_chunk$set(cache = TRUE)

```

## The Command Line

### The Big Picture

As William Shotts the author of *[The Linux Command Line](http://linuxcommand.org/tlcl.php)* put it:

> graphical user interfaces make easy tasks easy, while command-line interfaces make difficult tasks possible.

### Why bother using the command line?

Suppose that we want to create a plain text file that contains the word "test." If we want to do this in the command line, you need to know the following commands.

1. `echo`: "Write arguments to the standard output" This is equivalent to using a text editor (e.g., nano, vim, emacs) and writing something.

2. `> test` Save the expression in a file named test.

We can put these commands together like the following:

```sh

echo "sth" > test

```

Don't worry if you are worried about memorizing these and more commands. Memorization is a far less important aspect of learning programming. In general, if you don't know what a command does, just type `<command name> --help.` You can do `man <command name>` to obtain further information. Here, `man` stands for manual. If you need more user-friendly information, please consider using [`tldr`](https://tldr.sh/).

Let's make this simple case complex by scaling up. Suppose we want to make 100 duplicates of the `test` file. Below is the one-line code that performs the task!

```sh

for i in {1..100}; do cp test "test_$i"; done

```

Let me break down the seemingly complex workflow.

1. `for i in {1..100}.` This is for loop. The numbers 1..100 inside the curly braces `{}` indicates the range of integers from 1 to 100. In R, this is equivalent to for (i in 1:100) {}

2. `;` is used to use multiple commands without making line breaks. ; works in the same way in R.

3. `$var` returns the value associated with a variable. Type `name=<Your name>`. Then, type `echo $name.` You should see your name printed. Variable assignment is one of the most basic things you'll learn in any programming. In R, we do this by using ->

If you have zero experience in programming, I might have provided too many concepts too early, like variable assignment and for loop. However, you don't need to worry about them at this point. We will cover them in the next chapter.

I will give you one more example to illustrate how powerful the command line is. Suppose we want to find which file contains the character "COVID." This is equivalent to finding a needle in a haystack. It's a daunting task for humans, but not for computers. Commands are verbs. So, to express this problem in a language that computers could understand, let's first find what command we should use. Often, a simple Google or [Stack Overflow](https://stackoverflow.com/) search leads to an answer.

In this case, `grep` is the answer (there's also grep in R). This command finds PATTERNS in each FIEL. What follows - are options (called flags): `r` (recursive), `n` (line number), `w` (match only whole words), `e` (use patterns for matching). `rnw` are for output control and `e` is for pattern selection.

So, to perform the task above, you just need one-line code: `grep -r -n -w -e "COVID''`

**Quick reminders**

- `grep`: command

- `-rnw -e`: flags

- `COVID`: argument (usually file or file paths)

Let's remove (=`rm`) all the duplicate files and the original file. `*` (any number of characters) is a wildcard (if you want to identify a single number of characters, use `?`). It finds every file whose name starts with `test_`.

```sh

rm test_* test

```

Enough with demonstrations. What is this black magic? Can you do the same thing using a graphical interface? Which method is more efficient? I hope that my demonstrations give you enough sense of why learning the command line could be incredibly useful. In my experience, mastering the command line helps automate your research process from end to end. For instance, you don't need to write files from a website using your web browser. Instead, you can run the `wget` command in the terminal. Better yet, you don't even need to run the command for the second time. You can write a Shell script (`*.sh`) that automates downloading, moving, and sorting multiple files.

### UNIX Shell

The other thing you might have noticed is that there are many overlaps between the commands and base R functions (R functions that can be used without installing additional packages). This connection is not coincident. UNIX preceded and influenced many programming languages, including R.

The following materials on UNIX and Shell are adapted from [the software carpentry](https://bids.GitHub.io/2015-06-04-berkeley/shell/00-intro.html.

#### Unix

UNIX is an **operating system + a set of tools (utilities)**. It was developed by AT & T employees at Bell Labs (1969-1971). From Mac OS X to Linux, many of the current operation systems are some versions of UNIX. Command-line INTERFACE is a way to communicate with your OS by typing, not pointing, and clicking.

For this reason, if you're using Max OS, then you don't need to do anything else to experience UNIX. You're already all set.

If you're using Windows, you need to install either GitBash (a good option if you only use Bash for Git and GitHub) or Windows Subsystem (highly recommended if your use case goes beyond Git and GitHub). For more information, see [this installation guideline](https://GitHub.com/PS239T/spring_2021/blob/main/B_Install.md) from the course repo. If you're a Windows user and don't use Windows 10, I recommend installing [VirtualBox](https://www.virtualbox.org/).

UNIX is old, but it is still mainstream, and it will be. Moreover, [the UNIX philosophy](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix_philosophy) ("Do One Thing And Do It Well")---minimalist, modular software development---is highly and widely influential.

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/tc4ROCJYbm0" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p>AT&T Archives: The UNIX Operating System</p>

```

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/xnCgoEyz31M" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p>Unix50 - Unix Today and Tomorrow: The Languages </p>

```

#### Kernel

The kernel of UNIX is the hub of the operating system: it allocates time and memory to programs. It handles the [filestore](http://users.ox.ac.uk/~martinw/unix/chap3.html) (e.g., files and directories) and communications in response to system calls.

#### Shell

The shell is an interactive program that provides an interface between the user and the kernel. The shell interprets commands entered by the user or supplied by a Shell script and passes them to the kernel for execution.

#### Human-Computer interfaces

At a high level, computers do four things:

- run programs

- store data

- communicate with each other

- interact with us (through either CLI or GUI)

#### The Command Line

This kind of interface is called a **command-line interface**, or CLI,

to distinguish it from the **graphical user interface**, or GUI, that most people now use.

The heart of a CLI is a **read-evaluate-print loop**, or REPL: when the user types a command and then presses the enter (or return) key, the computer reads it, executes it, and prints its output. The user then types another command, and so on until the user logs off.

If you're using RStudio, you can use terminal inside RStudio (next to the "Console"). (For instance, type Alt + Shift + M)

#### The Shell

This description makes it sound as though the user sends commands directly to the computer and sends the output directly to the user. In fact, there is usually a program in between called a **command shell**.

What the user types go into the shell; it figures out what commands to run and orders the computer to execute them.

Note, the shell is called *the shell*: it encloses the operating system to hide some of its complexity and make it simpler to interact with.

A shell is a program like any other. What's special about it is that its job is to run other programs rather than do calculations itself. The commands are themselves programs: when they terminate, the shell gives the user another prompt ($ on our systems).

#### Bash

The most popular Unix shell is **Bash**, the Bourne Again Shell (so-called because it's derived from a shell written by Stephen Bourne --- this is what passes for wit among programmers). Bash is the default shell on most modern implementations of **Unix** and in most packages that provide Unix-like tools for Windows.

#### Why Shell?

Using Bash or any other shell sometimes feels more like programming than like using a mouse. Commands are terse (often only a couple of characters long), their names are frequently cryptic, and their output is lines of text rather than something visual like a graph.

On the other hand, the shell allows us to combine existing tools in powerful ways with only a few keystrokes and set up pipelines to handle large volumes of data automatically.

In addition, the command line is often the easiest way to interact with remote machines (explains why we learn Bash before learning Git and GitHub). If you work in a team and your team manages data in a remote server, you will likely need to get access the server via something like `ssh` (I will explain this when I explain `git`) and access a SQL database (this is the subject of the final chapter).

#### Our first command

The part of the operating system responsible for managing files and directories is called the **file system**. It organizes our data into files, which hold information, and directories (also called "folders"), which hold files or other directories.

Several commands are frequently used to create, inspect, rename, and delete files and directories. To start exploring them, let's open a shell window:

```sh

jae@jae-X705UDR:~$

```

Let's demystify the output above. There's nothing complicated.

- jae: a specific user name

- jae-X705UDR: your computer/server name

- `~`: current directory (`~` = home)

- `$`: a **prompt**, which shows us that the shell is waiting for input; your shell may show something more elaborate.

Type the command `whoami,` then press the Enter key (sometimes marked Return) to send the command to the shell.

The command's output is the ID of the current user, i.e., it shows us who the shell thinks we are:

```sh

$ whoami

# Should be your user name

jae

```

More specifically, when we type `whoami` the shell, the following sequence of events occurs behind the screen.

1. Finds a program called `whoami`,

2. Runs that program,

3. Displays that program's output, then

4. Displays a new prompt to tell us that it's ready for more commands.

#### Communicating to other systems

In the next unit, we'll focus on the structure of our own operating systems. But our operating systems rarely work in isolation; we often rely on the Internet to communicate with others! You can visualize this sort of communication within your own shell by asking your computer to `ping` (based on the old term for submarine sonar) an IP address provided by Google (8.8.8.8); in effect, this will test whether your Internet is working.

```sh

$ ping 8.8.8.8

```

Note: Windows users may have to try a slightly different alternative:

```sh

$ ping -t 8.8.8.8

```

(Thanks [Paul Thissen](http://www.paulthissen.org/) for the suggestion!)

#### File system organization

Next, let's find out where we are by running a `pwd` command (**print working directory**).

At any moment, our **current working directory** is our current default directory, i.e., the directory that the computer assumes we want to run commands in unless we explicitly specify something else.

Here, the computer's response is `/home/jae,` which is the **home directory**:

```sh

$ pwd

/home/jae

```

**Additional tips**

You can also download files to your computer in the terminal.

1. Install wget utility

```sh

# sudo = super user

sudo apt-get install wget

```

2. Download target files

```sh

wget https://download1.rstudio.org/desktop/bionic/amd64/rstudio-1.4.1103-amd64.deb

```

> #### Home Directory

>

> The home directory path will look different on different operating systems. For example, on Linux, it will look like `/home/jae,` and on Windows, it will be similar to `C:\Documents and Settings\jae.` Note that it may look slightly different for different versions of Windows.

> #### whoami

>

> If the command to find out who we are is `whoami,` the command to find out where we are ought to be called `whereami,` so why is it `pwd` instead? The usual answer is that in the early 1970s, when Unix was first being developed, every keystroke counted: the devices of the day were slow, and backspacing on a teletype was so painful that cutting the number of keystrokes to cut the number of typing mistakes was a win for usability. The reality is that commands were added to Unix one by one, without any master plan, by people who were immersed in its jargon.

>

> The good news: because these basic commands were so integral to the development of early Unix, they have stuck around and appear (in some form) in almost all programming languages.

> If you're working on a Mac, the file structure will look similar, but not identical. The following image shows a file system graph for the typical Mac.

We know that our current working directory `/home/jae` is stored inside `/home` because `/home` is the first part of its name. Similarly, we know that `/home` is stored inside the root directory `/` because its name begins with `/`.

#### Listing

Let's see what's in your home directory by running `ls` (**list files and directories):

```sh

$ ls

Applications Dropbox Pictures

Creative Cloud Files Google Drive Public

Desktop Library Untitled.ipynb

Documents Movies anaconda

Downloads Music file.txt

```

`ls` prints the names of the files and directories in the current directory in alphabetical order, arranged neatly into columns.

We can make `ls` more useful by adding flags. For instance, you can make your computer show only directories in the file system using the following command. Here `-F` flag classifies files based on some types. For example, `/` indicates directories.

```sh

ls -F /

```

The leading `/` tells the computer to follow the path from the file system's root, so it always refers to exactly one directory, no matter where we are when we run the command.

If you want to see only directories in the current working directory, you can do the following. (Remember `^`? This wildcard identifies a single number of characters. In this case, `d'.)

```sh

ls -l | grep "^d"

```

What if we want to change our current working directory? Before we do this, `pwd` shows us that we're in `/home/jae,` and `ls` without any arguments shows us that directory's contents:

```sh

$ pwd

/home/jae

$ ls

Applications Dropbox Pictures

Creative Cloud Files Google Drive Public

Desktop Library Untitled.ipynb

Documents Movies anaconda

Downloads Music file.txt

```

Use relative paths (e.g., `../spring_2021/references.md`) whenever it's possible so that your code is not dependable on how your system is configured.

**Additional tips**

How can I find pdf files in `Downloads` using the terminal? Remember `*` wildcard?

```sh

cd Downloads/

find *.pdf

```

Also, note that you don't need to type every character. Type the first few characters, then press TAB (autocomplete). This is called **tab-completion**, and we will see it in R as we go on.

#### Moving around

We can use `cd` (**change directory**) followed by a directory name to change our working directory.

```sh

$ cd Desktop

```

`cd` doesn't print anything, but if we run `pwd` after it, we can see that we are now in `/home/jae/Desktop.`

If we run `ls` without arguments now, it lists the contents of `/home/jae/Desktop,` because that's where we now are:

```sh

$ pwd

/home/jae/Desktop

```

We now know how to go down the directory tree: how do we go up? We could use an absolute path:

```sh

$ cd /home/jae/

```

but it's almost always simpler to use `cd ..` to go up one level:

```sh

$ pwd

/home/jae/Desktop

$ cd ..

```

`..` is a special directory name meaning "the directory containing this one," or more succinctly, the **parent** of the current directory. Sure enough, if we run `pwd` after running `cd ..`, we're back in `/home/jae/`:

```sh

$ pwd

/home/jae/

```

The special directory `..` doesn't usually show up when we run `ls`. If we want to display it, we can give `ls` the `-a' flag:

```sh

$ ls -a

. .localized Shared

.. Guest rachel

```

`-a' stands for "show all"; it forces `ls` to show us file and directory names that begin with `.`, such as `..`.

> #### Hidden Files: For Your Own Protection

>

> As you can see, many other items just appeared when we enter `ls -a'. These files and directories begin with `.` followed by a name. Usually, files and directories hold important programmatic information. They are kept hidden so that users don't accidentally delete or edit them without knowing what they're doing.

As you can see, it also displays another special directory that's just called `.`, which means "the current working directory". It may seem redundant to have a name for it, but we'll see some uses for it soon.

**Additional tips**

The above navigating exercises help us know about `cd` command, but not very exciting. So let's do something more concrete and potentially useful. Let's say you downloaded a file using your web browser and locate that file. How could you do that?

Your first step should be learning more about the `ls` command. You can do that by Googling or typing `ls --help.` By looking at the documentation, you can recognize that you need to add `-t` (sort by time). Then, what's `|`? It's called pipe, and it chains commands. For instance, if `<command 1> | <command 2>`, then command1's output will be command2's input. `head` list the first ten lines of a file. `-n1` flag makes it show only the first line of the output (n1).

```sh

# Don't forget to use TAB completion

cd Downloads/

ls -t | head -n1

```

Yeah! We can do more cool things. For example, how can you find the most recently downloaded PDF file? You can do this by combining the two neat tricks you learned earlier.

```sh

ls -t | find *.pdf | head -n1

```

#### Creating, copying, removing, and renaming files

##### Creating files

1. First, let's create an empty directory named exercise

```sh

mkdir exercise

```

2. You can check whether the directory is created by typing `ls`. If the print format is challenging to read, add `-l` flag. Did you notice the difference?

3. Let's move to the `exercise` subdirectory and create a file named test

```sh

cd exercise ; touch test ; ls

```

4. Read test

```sh

cat test

```

5. Hmn. It's empty. Let's add something there. `>` = overwrite

```sh

echo "something" > test ; cat test

```

6. Yeah! Can you add more? `>>` = append

```sh

echo "anything" >> test ; cat test

```

7. Removing "anything" from `test` is a little bit more complex because you need to know how to use `grep` (remember that we used this command in the very first example). Here, I just demonstrate that you can do this task using Bash, and let's dig into this more when we talk about working with text files.

```sh

grep -v 'anything' test

```

##### Copying and Removing Files

1. Can we make a copy of `test`? Yes!

```sh

cp test test_1; cat

```

2. Can we make 100 copies of `test?` Yes!

You can do this

```sh

cp test test_1

cp test test_2

cp test test_3

...

```

or

```sh

for i in {1..100}; do cp test "test_$i"; done

```

Which one do you like? (Again, don't focus on for loop. We'll learn it and other similar tools to deal with iterations in the later chapters.)

3. Can you remove all of the `test_` files?

You can do this

```sh

rm test_1

rm test_2

rm test_3

...

```

or

```

rm test_*

```

Which one do you like?

4. Let's remove the directory.

```sh

cd ..

rm exercise/

```

The `rm` command should not work because `exercise` is not a file. Type `rm --help` and see which flag will be helpful. It might be `-d' (remove empty directories).

```

rm -d exercise/

```

Oops. Still not working because the directory is not empty. Try this. Now, it works.

```

rm -r exercise/

```

What's `-r`? It stands for recursion (e.g., Recursion is a very powerful idea in programming and helps solve complex problems. We'll come back to it many times (e.g., `purrr::reduce()` in R).

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Mv9NEXX1VHc" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p> What on Earth is Recursion? - Computerphile </p>

```

##### Renaming files

1. Using `mv`

First, we will learn how to move files and see how it's relevant for renaming files.

```sh

# Create two directories

mkdir exercise_1 ; mkdir exercise_2

# Check whether they were indeed created

find exer*

# Create an empty file

touch exercise_1/test

# Move to exercise_1 and check

cd exercise_1 ; ls

# Move this file to exercise_2

mv test ../exercise_2

# Move to exercise_2 and check

cd exercise_2 ; ls

```

What `mv` has something to do with renaming?

* [mv] [source] [destination]

```sh

mv test new_test ; ls

```

2. Using `rename`

`mv` is an excellent tool to rename one file. But how about renaming many files? (Note that your pwd is still `exercise_2` where you have the `new_test` file.)

```sh

for i in {1..100}; do cp new_test "test_$i.csv"; done

```

Then install `rename`. Either `sudo apt-get install -y rename` or `brew install rename` (MacOS).

Basic syntax: rename [flags] perlexpr (Perl Expression) files. Note that [Perl](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perl) is another programming language.

```sh

# Rename every csv file to txt file

rename 's/.csv/.txt/' *.csv

# Check

ls -l

```

The key part is `s/.csv/.txt/` = `s/FIND/REPLACE`

Can you perform the same task using GUI? Yes, you can, but it would be more time-consuming. Using the command line, you did this via just one-liner(!). [Keith Brandnam](http://korflab.ucdavis.edu/Bios/bio_keithb.html) wrote an excellent book titled [UNIX and Perl to the Rescue! (Cambridge University Press 2012)](https://www.amazon.com/Unix-Perl-Rescue-Keith-Bradnam/dp/0521169828) that discusses how to use UNIX and Perl to deal with massively large datasets.

#### Working with CSV and text files

1. Download a CSV file (Forbes World's Billionaires lists from 1996-2014). For more on the data source, see [this site](https://corgis-edu.github.io/corgis/csv/billionaires/).

```sh

wget https://corgis-edu.github.io/corgis/datasets/csv/billionaires/billionaires.csv

```

2. Read the first two lines. `cat` is printing, and `head` shows the first few rows. `-n2` limits these number of rows equals 2.

**Additional tips 1**

If you have a large text file, `cat` prints everything at once is inconvenient. The alternative is using `less.`

```sh

cat billionaires.csv | head -n2

```

3. Check the size of the dataset (2615 rows). So, there are 2014 observations (n-1 because of the header). `wc` prints newline, word, and byte counts for each file. If you run `wc` without `-l` flag, you get the following: `2615 (line) 20433 (word) 607861 (byte) billionaires.csv`

```sh

wc -l billionaires.csv

```

4. How about the number of columns? `sed` is a stream editor and very powerful when it's used to filter text in a pipeline. For more information, see [this article](https://www.gnu.org/software/sed/manual/sed.html). You've already seen `s/FIND/REPLACE.` Here, the pattern we are using is `s/delimiter/\n/g.` We've seen that the delimiter is `,` so that's what I plugged in the command below.

```sh

head -1 billionaires.csv | sed 's/,/\n/g' | nl

```

**Additional tips 2**

The other cool command for text parsing is `awk.` This command is handy for filtering.

1. This is the same as using `cat.` So, what's new?

```sh

awk '{print}' billionaires.csv

```

2. This is new.

```sh

awk '/China/ {print}' billionaires.csv

```

3. Let's see only the five rows. We filtered rows so that every row in the final dataset contains 'China.'

```sh

awk '/China/ {print}' billionaires.csv | head -n5

```

4. You can also get the numbers of these rows.

```sh

awk '/China/ {print NR}' billionaires.csv

```

#### User roles and file permissions

1. If you need admin access, use `sudo.` For instance, `sudo apt-get install <package name>` installs the package.

2. To run a Shell script (.sh), you need to change its file mode. You can make the script executable by typing `chmod +x <Shell script>.` Then, you can run it by typing `./pdf_copy_sh.` `.` refers to the current working directory. Other options: `sh pdf_copy_sh.` or `bash pdf_copy_sh.` I use `./pdf_copy_sh.`

#### Writing your first Shell script (.sh)

Finally, we're learning how to write a Shell script (a file that ends with .sh). Here I show how to write a Shell script that creates a subdirectory called `/pdfs` under `/Download` directory, then find PDF files in `/Download` and copy those files to `pdfs.` Essentially, this Shell script creates a backup. Name this Shell script as 'pdf_copy.sh.'

```sh

#!/bin/sh # Stating this is a Shell script.

mkdir /home/jae/Downloads/pdfs # Obviously, in your case, this file path should be incorrect.

cd Download

cp *.pdf pdfs/

echo "Copied pdfs"

```

**Additional tips**

Using Make [TBD]

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/aw9wHbFTnAQ" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p> Using make and writing Makefile (in C++ or C) by Programming Knowledge </p>

```

### References

- [The Unix Workbench](https://seankross.com/the-unix-workbench/) by Sean Kross

- [The Unix Shell](http://swcarpentry.GitHub.io/shell-novice/), Software Carpentry

- [Data Science at the Command Line](https://www.datascienceatthecommandline.com/1e/) by Jeroen Janssens

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/QxpOKbv-KQU" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p> Obtaining, Scrubbing, and Exploring Data at the Command Line by Jeroen Janssens from YPlan, Data Council </p>

```

- [Shell Tools and Scripting](https://missing.csail.mit.edu/2020/shell-tools/), ./missing-semester, MIT

- [Command-line Environment](https://missing.csail.mit.edu/2020/command-line/), ./missing-semester, MIT

## Git and GitHub

### The Big Picture

**The most important point**

* Backup != Version control

* If you do version control, you need to save your **raw data** in your hard disk, external drive, or cloud, but nothing else. In other words, anything you are going to change should be subject to version control (also, it's not the same as saving your code with names like 20200120_Kim or something like that). Below, I will explain what version control is and how to do it using Git and GitHub.

### Version control system

According to [GitHub Guides](https://guides.GitHub.com), a version control system "tracks the history of changes as people and teams collaborate on projects together." Specifically, it helps to track the following information:

* Which changes were made?

* Who made the changes?

* When were the changes made?

* Why were changes needed?

Git is a case of a [distributed version control system](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_version_control), common in open source and commercial software development. This is no surprise given that Git [was originally created](https://lkml.org/lkml/2005/4/6/121) to deal with Linux kernel development.

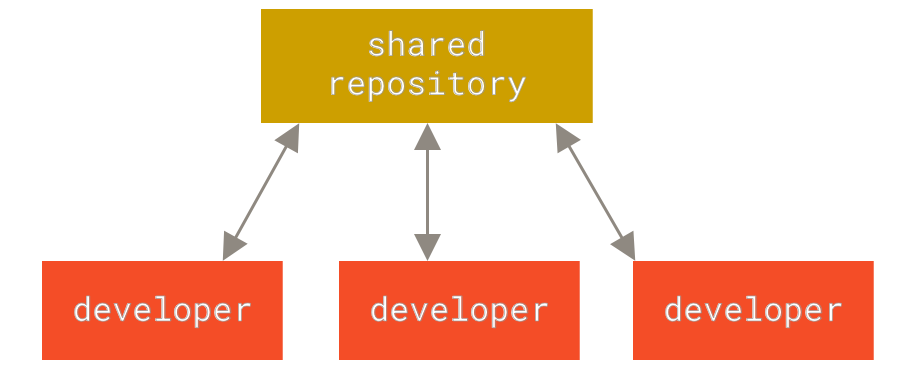

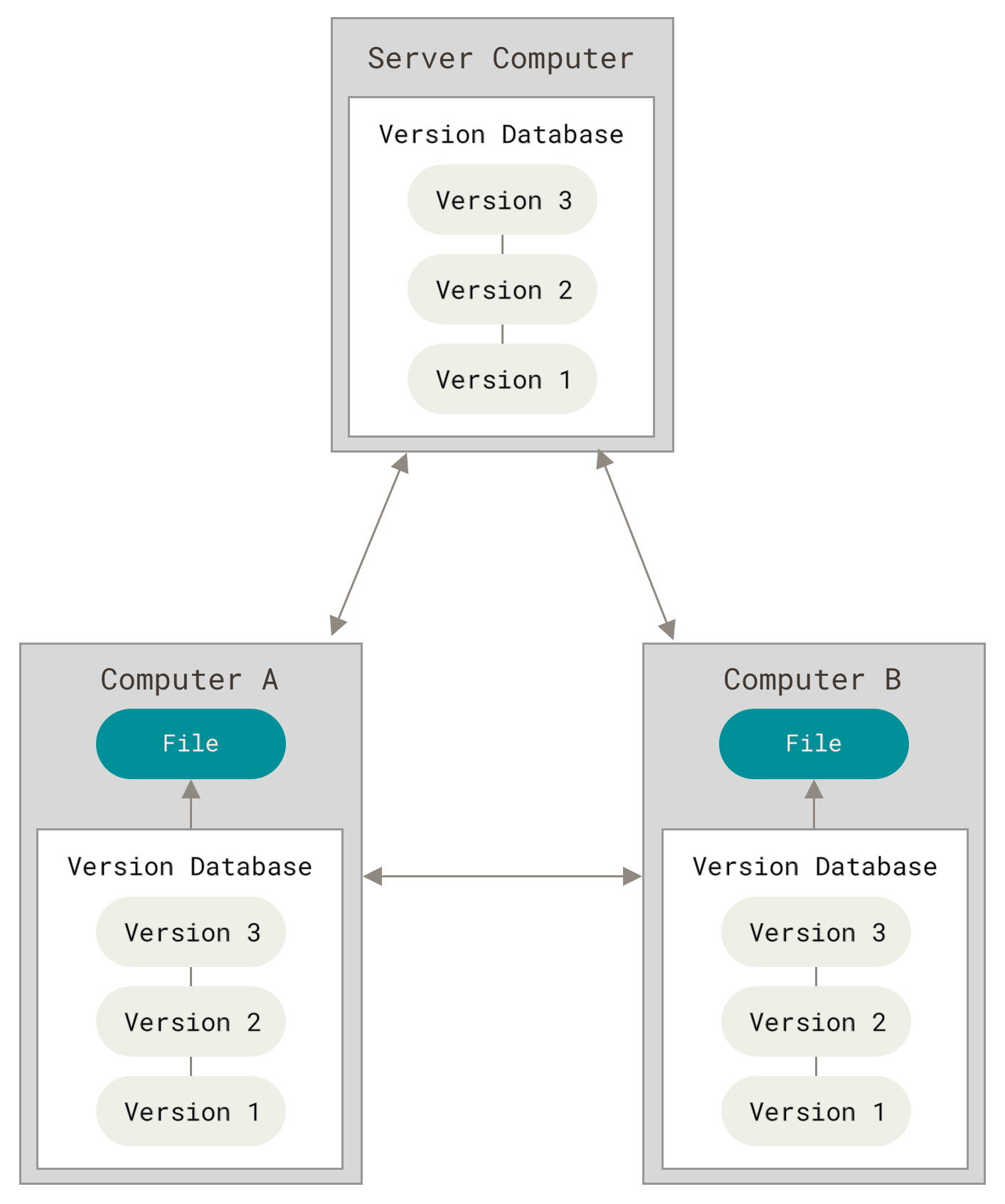

The following images, from [Pro Git](git-scm.com), show how a centralized (e.g., CVS, Subversion, and Perforce) and decentralized VCS (e.g., Git, Mercurial, Bazzar or Darcs) works differently.

Figure 2. Centralized VCS.

Figure 3. Decentralized VCS.

For more information on the varieties of version control systems, please read [Petr Baudis's review](https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4490/4c70bc91e1bed4fe02b9e2282f031b7c90ea.pdf) on that subject.

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/PFwUHTE6mFc" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p> Webcast • Introduction to Git and GitHub • Featuring Mehan Jayasuriya, GitHub Training & Guides </p>

```

For more information, watch the following video:

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/u6G3fbmpWr8" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p> The Basics of Git and GitHub, GitHub Training & Guides </p>

```

### Setup

#### Signup

1. Make sure you have installed Git ([[tutorial]](https://happygitwithr.com/install-git.html#install-git)).

```sh

git --version

# git version 2.xx.x

```

2. If you haven't, please sign up for a GitHub account: https://github.com/

- If you're a student, please also sign up for GitHub Student Developer Pack: https://education.github.com/pack Basically, you can get a GitHub pro account for free (so why not?).

3. Access GitHub using Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) or Secure Shell (SSH).

**HTTPS**

1. Create a personal access token. Follow this guideline: https://docs.github.com/en/github/authenticating-to-github/creating-a-personal-access-token

2. Store your credential somewhere safe. You can use an R package like this [gitcreds](https://gitcreds.r-lib.org/) and [credentials](https://docs.ropensci.org/credentials/) to do so.

```{r eval = FALSE}

pacman::p_load(gitcreds)

# First time only

gitcreds_set()

# Check

gitcreds_get()

```

3. If you get asked to provide your password when you pull or push, the password should be your GitHub token (to be precise, personal access token).

**SSH**

If possible, I highly recommend using SSH. Using SSH is safer and also makes connecting GitHub easier. SSH has two keys (public and private). The public key could be stored on any server (e.g., GitHub) and the private key could be saved in your client (e.g., your laptop). Only when the two are matched, the system unlocks.

1. First, read [this tutorial](https://docs.github.com/en/github/authenticating-to-github/connecting-to-github-with-ssh ) and create SSH keys.

2. Second, read [this tutorial](https://happygitwithr.com/ssh-keys.html) and check the keys and provide the public key to GitHub and add the private key to ssh-agent.

Next time, if you want to use SSH, remember the following.

```sh

# SSH

[email protected]:<user>/<repo>.git

# HTTPS

https://github.com/<user>/<repo>.git

```

**Additional tips**

When you try to clone a git repo, you can get the links like the above by clicking the CODE action button on GitHub.

#### Configurations

1. Method 1: using the terminal

```sh

# User name and email

$ git config --global user.name "Firstname Lastname"

$ git config --global user.email [email protected]

```

2. Method 2: using RStudio (if you insist on using R)

```{r eval=FALSE}

pacman::p_load(usethis)

use_git_config(user.name = "<Firstname Lastname>",

user.email = "<[email protected]>")

```

You're all set!

### Cloning a repository

Let's clone a repository. The following address is the course I co-taught in Spring 2021.

```sh

git clone https://github.com/PS239T/spring_2021

```

If you `cd spring_2021/` you can move to the cloned course repository. Cloning: copying a public GitHub repo (remote) -> Your machine

If I made some changes in the remote repo, you can apply them to your local copy by typing `git pull.` You may get promoted to provide a password. Then type the following to switch the remote URL's address from HTTPS to SSH.

```sh

git remote set-url origin [email protected]:[user]/[repo]

```

If this doesn't work and get the following error, try the following (assuming that your SSH key was removed). If you're using Mac, try this instead: `ssh-add -k ~/.ssh/id_rsa`

```sh

ssh-add ~/.ssh/id_rsa

```

If you still face difficulties, see [this stack overflow thread](https://stackoverflow.com/questions/13509293/git-fatal-could-not-read-from-remote-repository).

If you screwed something up in your local copy, you can just overwrite the local copy using the remote repo and make it exactly looks like the latter.

```sh

# Download content from a remote repo

git fetch origin

# Going back to origin/main

git reset --hard origin/main

# Remove local files

git clean -f

```

Note that the default branch name changed from master to main: https://github.com/github/renaming (Finally!) For this reason, if you're interacting with old repositories, the main branch name is likely to master.

**Additional tips**

You can see cloning and forking on GitHub, and they sound similar. Let me differentiate them.

* Cloning: creating a local copy of a **public** GitHub repo. In this case, you have writing access to the repo.

* Forking (for open source projects): creating a copy of a **public** GitHub repo to your GitHub account, then you can clone it. In this case, you don't have writing access to the repo. You need to create pull requests if you want your changes reflected in the original repo. Don't worry about pull requests, as I will explain the concept shortly. For more information, see [this documentation](https://docs.github.com/en/desktop/contributing-and-collaborating-using-github-desktop/cloning-and-forking-repositories-from-github-desktop).

### Making a repository

Create a new directory and move there.

Then initialize

```sh

# new directory

$ mkdir code_exercise

# move

$ cd code_exercise

# initialize

$ git init

```

Alternatively, you can create a Git repository via GitHub and then clone it on your local machine. Perhaps, it is an easier path for new users (I also do this all the time). I highly recommend adding README (more on why we do this in the following subsection).

```sh

$ git clone /path/to/repository

```

**Additional tips**

If you're unfamiliar with basic Git commands, please refer to [this Git cheat sheet](http://rogerdudler.GitHub.io/git-guide/files/git_cheat_sheet.pdf).

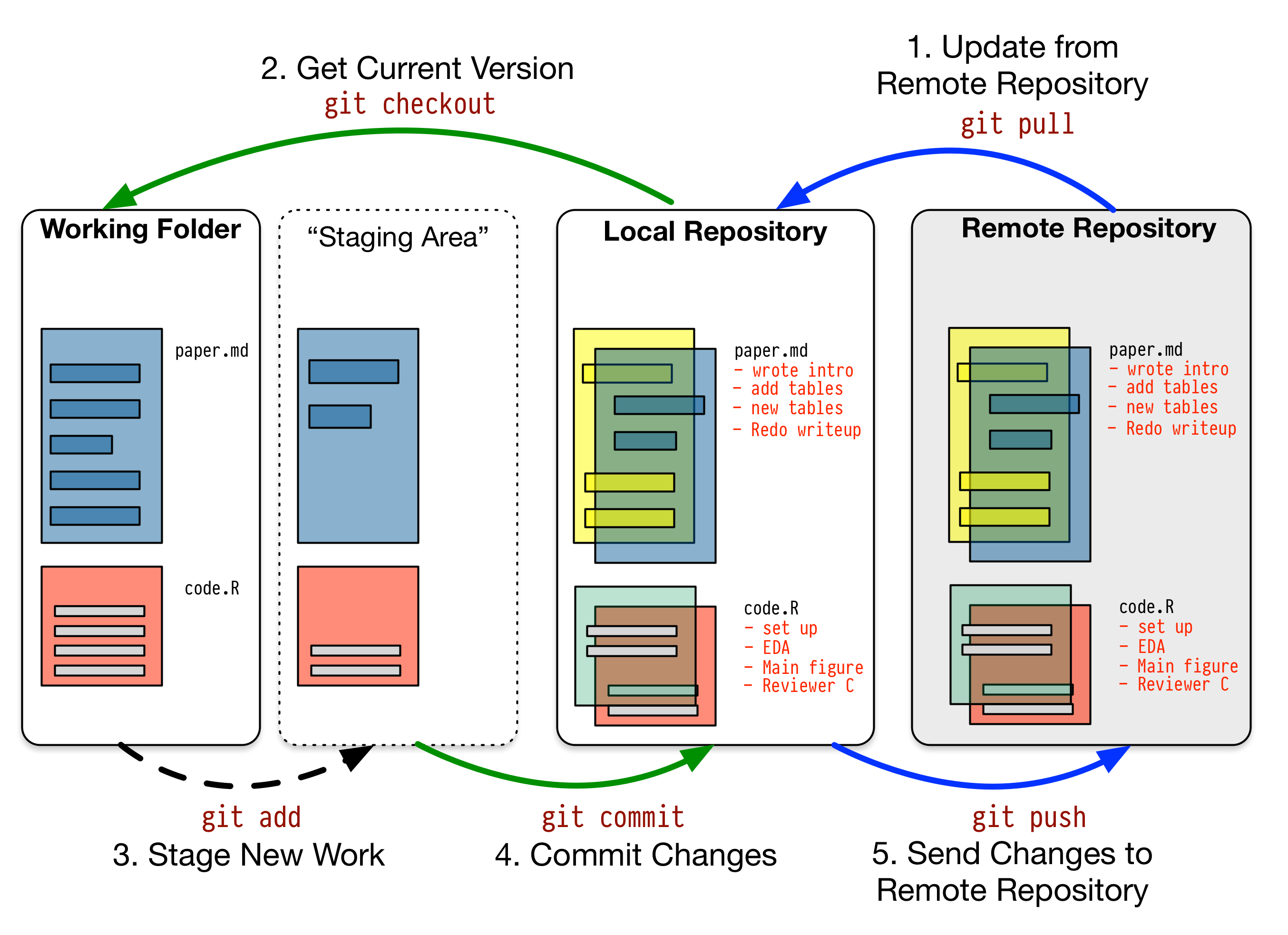

### Commit changes

These features show how Git works as a version control system.

If you edited files or added new ones, you need to update your repository. In Git terms, this action is called committing changes.

My current pwd is `spring_2021`. I created a text file named `test` containing text `jae.` You can check the file exists by typing `find "test```.

The following is a typical workflow to reflect this change to the remote.

```sh

$ git status # check what's changed.

$ git add . # update every change. In Git terms, you're staging.

$ git add file_name # or stage a specific file.

$ git commit -m "your comment" # your comment for the commit.

$ git push origin main # commit the change. Origin is a default name given to a server by Git. `origin main` are optional.

```

Another image from [Pro Git](https://git-scm.com/about/staging-area) nicely illustrates this process.

If you made a mistake, don't panic. You can't revert the process.

```sh

git reset --soft HEAD~1 # if you still want to keep the change, but you go back to t-1

git reset --hard HEAD~1 # if you're sure the change is unnecessary

```

Writing an informative commit is essential. To learn how to do this better, see the following video:

```{=html}

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/m0t1mOeAJgs" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p> Your Commits Should Tell a Story • Featuring Eliza Brock Marcum, GitHub Training & Guides </p>

```

### Push and pull (or fetch)

These features show how Git works as a collaboration tool.

If you have not already done it, let's clone the PS239T directory on your local machine.

```sh

$ git clone https://github.com/PS239T/spring_2021 # clone

```

**Additional tips 1**

If you try to remove `spring_2021` using `rm -r spring_2021/`, you will get an error about the write-protected regular file. Then, try `rm -rf spring_2021/`.

Then, let's learn more about the repository.

```sh

$ git remote -v

```

You should see something like the following:

```sh

origin [email protected]:PS239T/spring_2021 (fetch)

origin [email protected]:PS239T/spring_2021 (push)

```

If you want to see more information, then type `git remote show origin.`

Previously, we learned how to send your data to save in the local machine to the remote (the GitHub server). You can do that by editing or creating files, committing, and typing **git push**.

Instead, if you want to update your local data with the remote data, you can type **git pull origin** (something like pwd in bash). Alternatively, you can use fetch (retrieve data from a remote). Git retrieves the data and merges it into your local data when you do that.

```sh

$ git fetch origin

```

**Additional tips 2**

Developers usually use PR to refer pull requests. When you are making PRs, it's recommended to scope down (small PRs) because they are easier on reviewers and to test. To learn about how to accomplish this, see [this blog post](https://www.netlify.com/blog/2020/03/31/how-to-scope-down-prs/) by Sarah Drasner.

### Branching

It's an advanced feature of Git's version control system that allows developers to "diverge from the main line of development and continue to do work without messing with that main line," according to [Scott Chacon and Ben Straub](https://git-scm.com/book/en/v1/Git-Branching).

If you start working on a new feature, create a new branch.

```sh

$ git branch new_features

$ git checkout new_features

```

You can see the newly created branch by typing **git branch**.

In short, branching makes Git [works like](https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Getting-Started-Git-Basics) a mini file system.

### Other useful commands